Thoracic aortic dissections

Last edited on : 22/09/2024

A thoracic aortic dissection involves a tear in the intimal layer of the thoracic aorta's arterial wall, either circumferential or transverse, leading to the intrusion of pulsatile blood flow, progressively shearing the elastic fibers and forming a false lumen with progressive extension (typically downstream) between the intima and media. The condition can evolve towards rupture or spontaneous regression (thrombosis of the false lumen). Without treatment, the mortality rate is 90-95% within a year and it is rapidly fatal in case of rupture. It is a medical-surgical emergency.

It is caused by a tear in the intima that extends to the media or by hemorrhage into the media. The tear most commonly occurs on the right side of the aorta (higher pressure), often due to acute damage to the intima over an existing lesion in the media.

In some cases, the false lumen reconnects lower on the aorta with the true lumen through a distal intimal tear, and the dissection may stop, or the false lumen may thrombose.

The incidence is ~2/100,000 inhabitants per year and increases with age (peak at 60-70 years). The sex ratio is 2 men for every 1 woman.

Classification

The Stanford classification is preferred (it correlates best with severity, response to medical treatment alone, and thus the urgency of surgery):

- Type A: involves the ascending aorta (regardless of the entry point or extension). This is the most dangerous and most frequent form (85% of dissections).

- Type B: the ascending thoracic aorta is not involved in the dissection (15% of dissections).

The historical DeBakey classification is still widely used out of habit in the medical community:

- Type I: the dissection extends from the ascending aorta to at least the aortic arch and usually beyond.

- Type II: the dissection is limited to the ascending aorta.

- Type III: the dissection begins in the descending aorta. Extension is generally antegrade, but rarely it can progress retrograde (in which case, the entry point may exceptionally be in the abdominal aorta) to the aortic arch.

Etiologies and Risk Factors

For a dissection to follow an intimal lesion, a pre-existing alteration of the media must always be present:

- Atheromatous lesions, with the main risk factors being hypertension (present in 70% of patients), smoking, dyslipidemia, toxic substances (cocaine++), and age.

- Aortic aneurysm

- Cystic medial necrosis

- Connective tissue disorders: Marfan syndrome (aortic dissection being the leading cause of death in Marfan), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Inflammatory aortitis: Takayasu's arteritis, Horton’s disease, Behçet’s disease

- Valvular diseases: bicuspid aortic valve++

- Aortic coarctation

- Rarer causes include:

- Trauma (particularly at the aortic isthmus), surgery, and aortic catheterization

- Rupture of an intra-aortic balloon pump

- Pregnancy (third trimester)

Dissections may occur spontaneously on these pre-existing lesions, during a hypertensive episode, or following trauma or minor exertion.

Clinical Presentation and Natural History

Typical presentation of an acute dissection (< 15 days):

- Acute chest pain is the predominant symptom, tearing in nature, and transfixing between the shoulder blades or radiating to the lower back.

- Hypertension is common. The occurrence of hypotension is a marker of extreme severity (often progressing to death).

- Absence of peripheral pulse, blood pressure asymmetry, development of an aortic regurgitation murmur, syncope, neurological deficits, compression of adjacent tissues (lymph nodes, esophagus, bronchi, inferior vena cava, Claude-Bernard-Horner syndrome), potential pleural effusion...

- Less common: myocardial infarction (involvement of coronary ostia, especially the right coronary), signs of visceral or limb ischemia, strokes, or spinal cord ischemia.

- The onset of aortic insufficiency (murmur, drop in diastolic pressure, echographic signs) is the best indicator of a surgical emergency (type A dissection).

Typical presentation of a "sub-acute" and chronic dissection (> 15 days):

- Pain is generally in the background or absent. Secondary symptoms predominate.

Complications

The main complications of a dissection are :

- Aortic rupture

- Aortic valve insufficiency

- Retrograde extension to the coronary arteries

- Acute heart failure

- Thromboembolic events: strokes and spinal cord ischemia, acute limb ischemia, renal infarction, mesenteric infarction, peripheral emboli...

- Ischemia of organs due to reduced downstream blood flow

Main Anatomoclinical Evolutionary Presentations

Classic aortic dissection

This involves one or more breaches in the intima feeding flow into the false lumen, with tubular or helicoidal dissection. If there is an exit tear, the flow is under lower pressure. The entry point is located in the ascending aorta in 60% of cases, the aortic arch in 15%, and more distally in 25%.

Intramural hematoma

Cystic medial necrosis with rupture of the vasa vasorum, leading to intramural hemorrhage splitting the wall.

Localized dissection

Often described as a "contained dissection," where the tear quickly evolves into a mural thrombosis.

Penetrating ulcer

This involves the ulceration of an atheromatous plaque (mostly in the aortic arch or abdominal aorta). It can evolve into a stable condition, regress, or form a "pseudoaneurysm".

Differential Diagnosis

(See detailed article: Acute Chest Pain)

The differential diagnosis is broad and varies depending on the clinical presentation. It is typically related to acute chest pain but can sometimes mimic back pain, abdominal pain, or a neurological deficit.

Additional Tests

The diagnosis is primarily clinical, and further testing should not delay therapeutic management. The goals of testing are to:

- Confirm the diagnosis

- Classify the dissection (Is the ascending aorta involved?)

- Differentiate the true lumen from the false lumen

- Detect a thrombus in the false lumen

- Identify the number of entry points and any potential exit points

- Determine if the dissection is communicating

- Detect the presence of aortic valve insufficiency

- Identify any extravasation (pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, mediastinum)

- Determine whether aortic branches are affected (coronary, cervicobrachial, visceral)

- Rule out complications

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Routine procedure. It is usually normal. If ischemic signs are present, the differential diagnosis between isolated acute coronary syndrome or one secondary to dissection must be based on history, clinical examination, older ECGs, and cardiac ultrasound.

Blood Tests and Arterial Blood Gases

Includes hemato-CRP, electrolytes, troponins, coagulation profile, lipase, renal and liver function tests. These help to exclude differential diagnoses, identify complications, and provide a preoperative assessment.

Chest X-ray

Not necessary if the diagnosis is already considered probable. Otherwise, it can help in the differential diagnosis or provide positive indicators (in 80% of cases: widening of the aortic silhouette, sometimes with double contours. Possible pleural effusion, aortic calcifications, mediastinal widening, etc.).

Transthoracic and Transesophageal Echocardiography

This is a fundamental examination.

- Transthoracic:

- Visualizes the aortic valve, the aortic root, and the first few centimeters of the ascending aorta. Allows for an assessment of cardiac function and examination of the pericardium.

- Quick, easy, non-invasive BUT incomplete.

- Transesophageal:

- Similar observations but of better quality.

- The thoracic aorta is visualized down to the diaphragm. Sometimes the origin of the brachiocephalic vessels can be seen for a few centimeters.

- The flow in the false lumen is visible, as is thrombosis. Morphological features can be described.

- Performed under general anesthesia.

- Sometimes difficult to perform, not without risk, very uncomfortable in emergencies BUT complete.

Angio-CT Thoracic Scan

- CT scan with contrast and multiplanar reconstruction.

- Excellent characterization of the dissection.

- Drawbacks: poor visualization of the horizontal portion of the aortic arch, no coronary visualization, and difficulty assessing the aortic valve.

Thoracic Angio-MRI

Although less commonly used, results are considered similar to those of the angio-CT scan, but:

- It allows for imaging in all planes.

- No radiation exposure.

- Rarely available in emergencies.

- Time-consuming!

- Lower image quality.

Conventional Aortography

Due to the risks and the performance of the angio-CT scan, this technique is only used during therapeutic angiography for stent placement.

Therapeutic Management – Treatments

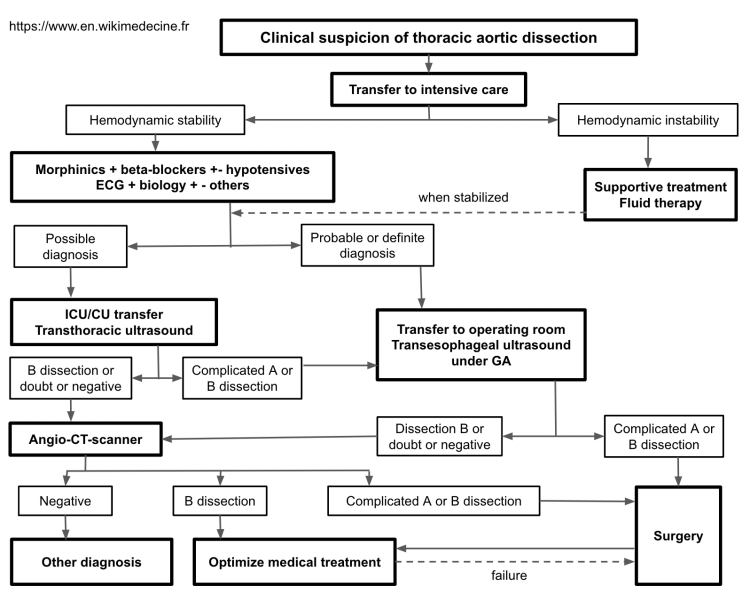

Example of a management plan:

Medical Management

Always necessary.

- Transfer to intensive care, general measures, morphine, arterial and urinary catheters.

- In the absence of shock:

- Always administer a beta-blocker (to reduce shearing forces). Example: metoprolol 5 mg IV every 15 minutes. Calcium channel blockers if contraindicated.

- +/- antihypertensives (e.g., clonidine 8 ampoules/24 hours and/or nitroprusside 0.2-0.3 mcg/kg/hour). If contraindicated, calcium channel blockers are preferred. Avoid direct vasodilators such as hydralazine to prevent worsening the shearing forces.

- The goal is to reduce systolic blood pressure (SBP) to around 100-110 mmHg, adjusted according to hemodynamic tolerance.

- In case of shock:

- Supportive treatment is required (intubation, massive fluid resuscitation, and blood transfusions). Surgery is rarely feasible, beta-blockers are obviously contraindicated, and the outcome is often fatal.

Discuss Urgent Surgical Indications

Once supportive measures have been initiated, a systematic discussion between the intensivist and vascular surgeon, with possible endovascular involvement, is required.

- General Surgical Indications:

- Type A dissections (involving the proximal aorta)

- Surgery involves placing a Dacron graft under cardiopulmonary bypass, plus aortic valve repair if needed.

- Complicated Type B dissections (aortic rupture, visceral or limb ischemia) or failure of medical treatment (uncontrollable hypertension, progressive dissection, or aortic dilation despite optimal medical management).

- Surgery involves placing a Dacron graft under cardiopulmonary bypass. Depending on the center’s expertise, an endovascular approach may be preferred.

- For any type of dissection, surgery is generally considered in Marfan patients.

- Type A dissections (involving the proximal aorta)

- For uncomplicated Type B dissections, an endovascular approach may be considered, but medical management alone is usually preferred. This decision depends on the specific case and the center’s expertise.

The difference in management is justified by a well-established difference in prognosis. With medical treatment alone, the mortality rate for Type A dissections is 61% at 1 year and 73% at 10 years. For Type B dissections, it is 9% at 1 year and 47% at 10 years.

Follow-up Care

- Long-term antihypertensive treatment (preferably a combination of a beta-blocker, calcium channel blocker, and ACE inhibitor. At minimum, a beta-blocker if there are no contraindications. Avoid direct vasodilators and beta-blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity) must be systematic.

- Avoid strenuous physical activity.

- Angiographic monitoring (++ angio-MRI) before discharge, at 1 month, at 6 months, at 1 year, and then annually.

Bibliography

EMC, Traité de cardiologie, 2018

Masuda Y, Prognosis of patients with medically treated aortic dissections, Circulation, 1991 Nov;84(5 Suppl):III7-13